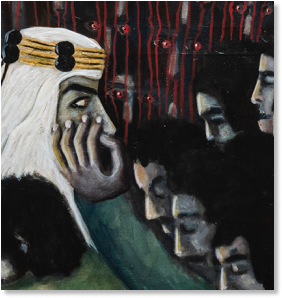

Louise Brunet is only 18 years old when she is recruited by a henchman of the

great silk merchant

Nicolas Portalis upon her release from prison in the Drôme region south of Lyon. On an icy

cold

morning in 1839 with few better alternatives, she embarks on the Heliopolis from Marseille

to

try

her luck in Lebanon. Eighteen other women all seeking the better life promised to them by

this

merchant of great repute also join the voyage. To the dismay of Portalis’s recruiter, some

appear

with their children. The additional cost of accommodating these unexpected extra travellers

will

become a matter of financial contention a few months later.

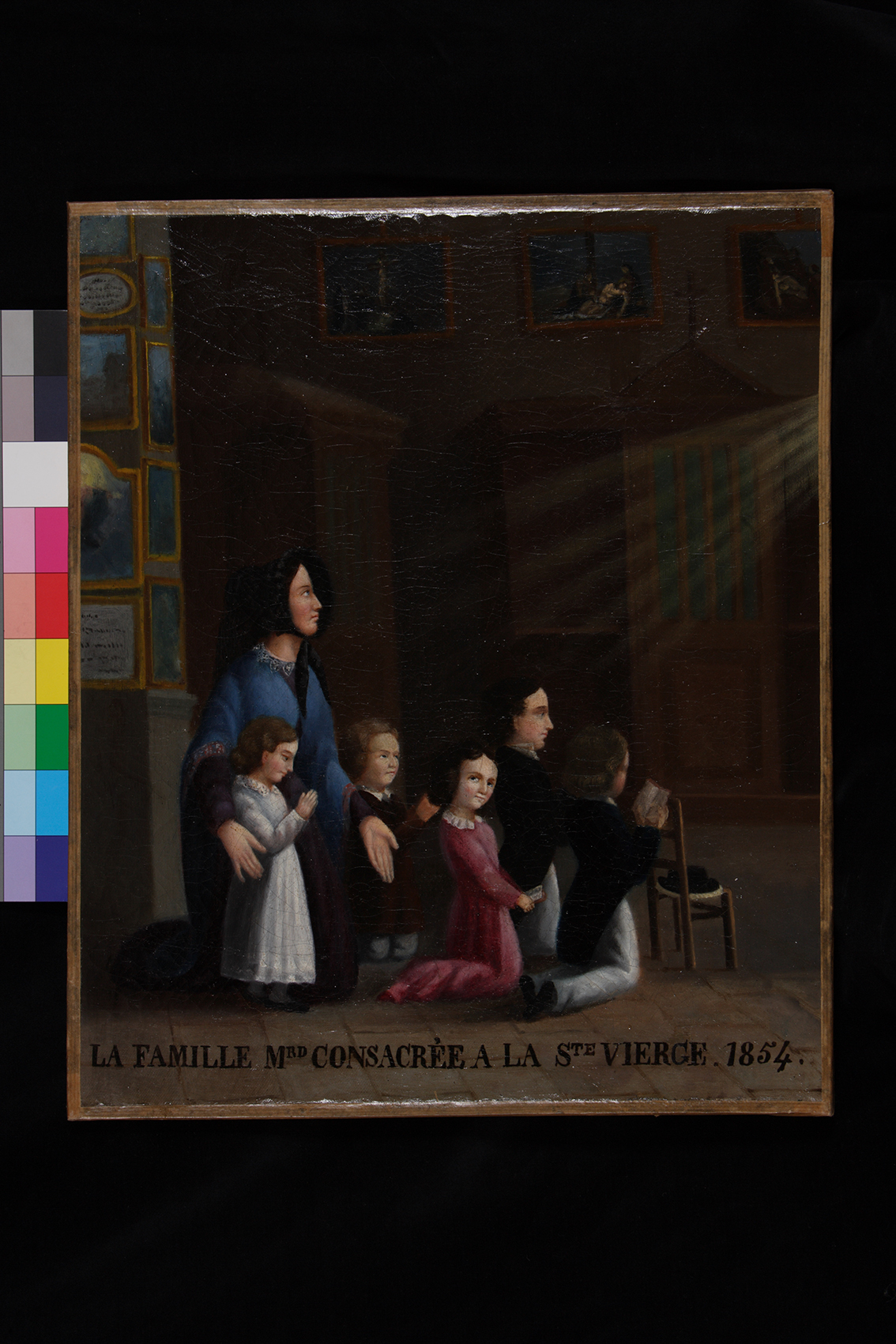

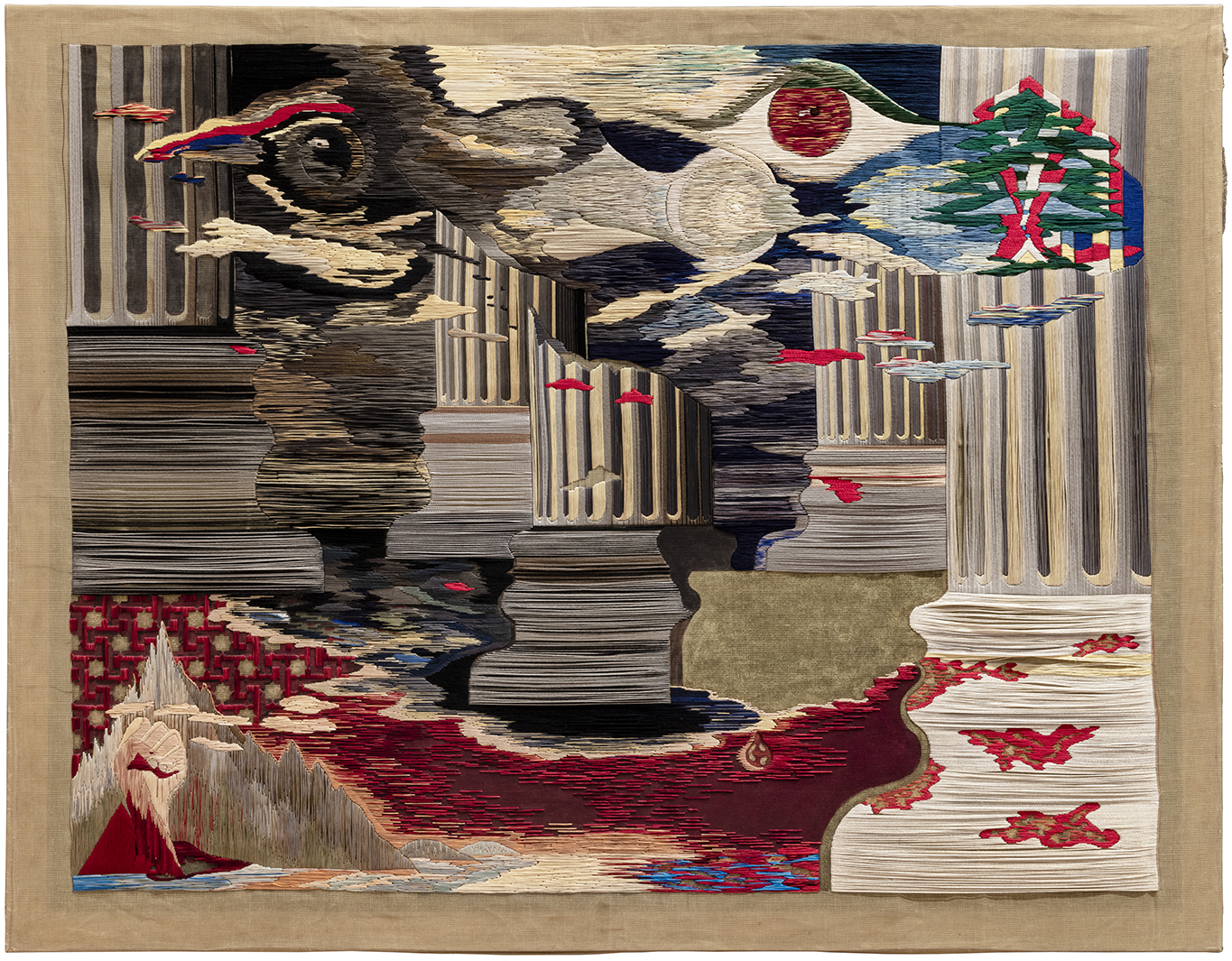

Portalis had recently hatched the idea of "importing" experienced spinners to launch his

business:

a major silk factory in the village of Btetir in Mount Lebanon. Lyon was an ideal breeding

ground

for this high quality workforce, but the city’s history of revolts would not make it easy

for

him.

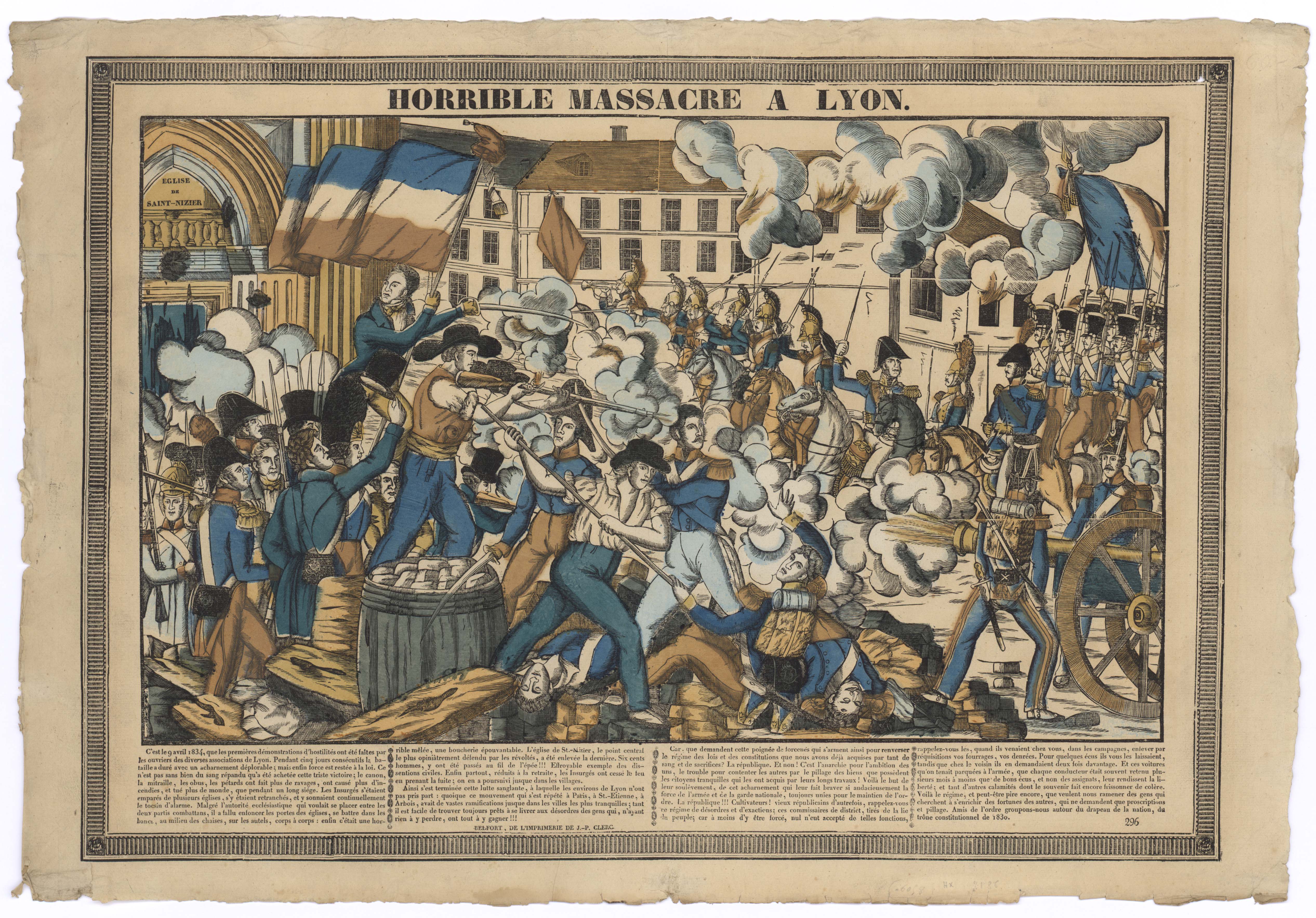

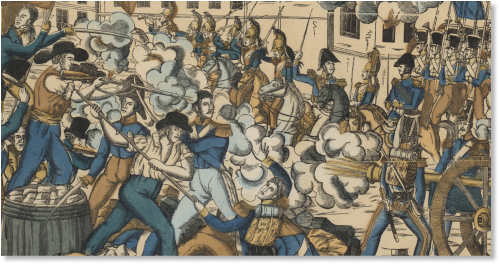

In April 1834 , in the hope of improving their living conditions, the silk workers, known

locally in

Lyon as canuts, had thrown the capital of Gauls into chaos during the second Canut revolt.

The

civil

unrest became so widespread that the French state was forced to intervene, sending armed

troops

from

Paris to reestablish order, which they had already done in 1831 and would do again in 1848.

The

Brunet household – built by a spinner to provide housing for his workers and who most likely

was

related to Louise – became a stronghold for the canuts. The revolt was ultimately suppressed

by

force. Louise Brunet was imprisoned along with over 10,000 other participants in the revolt.

However, as her story proves, the seed of her resolve against the established order was

deeply

rooted.

At some point during the voyage to Lebanon, the captain deviously suggests he no longer

wants to

deliver Louise and the other spinners to Portalis. Louise is forced to submit to him

sexually in

order to reach her final destination. A few months later, she writes to her sister to tell

her

about

the hell of her daily life. “It is a blessing that some of these women perished due to the

cholera

pandemic that had swept across Beirut upon our arrival,” Brunet laments. She tells her

sister

how

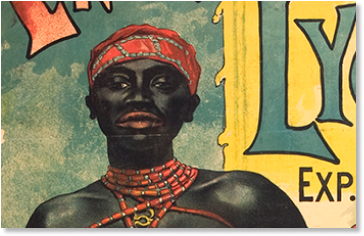

she has taught young Lebanese women not to put their health at risk in spinning mills. Many

of

these

women are actually six-year-old children. They were recruited from Jesuit and Lazarist

orphanages

financed by the affluent Lyon Silk merchants who own the factories. The most notorious among

them

were the spinning factories of Mourgue d’Algue in ‘Ayn Hamadé, Palluat and Testenoire et Cie

in

Al

Qrayyé, which would eventually be bought by Veuve Guérin et Fils. The latter, whose

factories

are

the largest with 558 basins spread over four buildings, are infamous for their collaboration

with

the sisters of the Filles de la Charité.

The working conditions are so bad that Louise foments a revolution with some of her peers

and

eventually flees. She is captured and once again finds herself imprisoned. Louise’s name

appears

once more in a letter addressed from Portalis to Nicolas Prosper Bourée, the newly installed

French

Consul General in Beirut. In the letter, Portalis refuses to pay for her expatriation. In

one

ambiguous passage from this correspondence – which can be found in the classified archives

of

the

French Ministry of Foreign Affairs as file number 92PO_A_28 – Portalis’ strongman Clément

Dreveton

proposes paying for Louise’s trip to the neighbouring island of Cyprus but declines to

finance

her

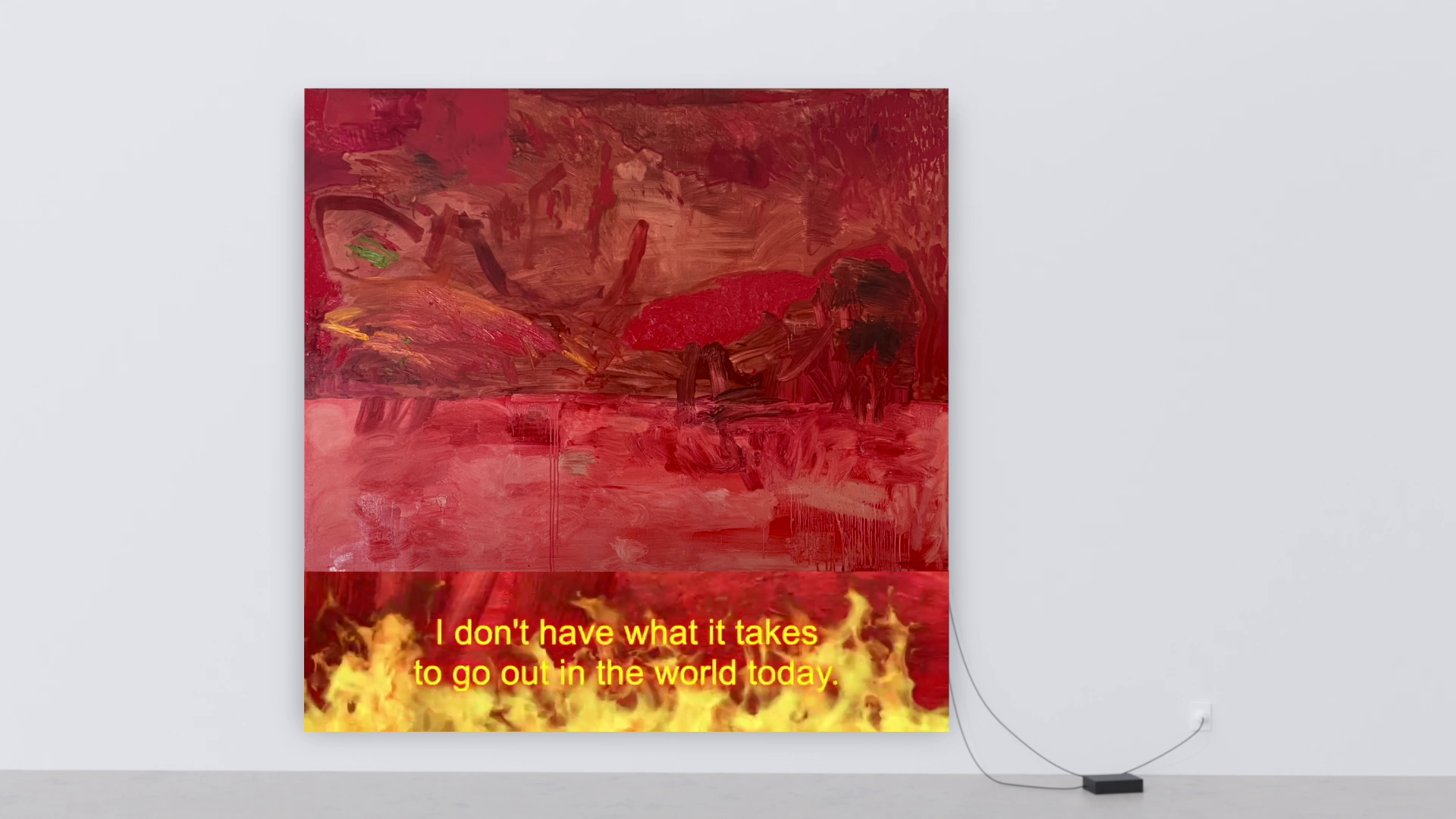

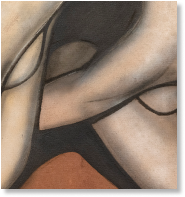

travels any further. Beyond this letter, Louise disappears. Resistant at heart, the image of

the

young woman dipping her skilled hands every day in bubbling chemicals to pull out thin

threads

of

silk is still haunting. Almost two hundred years later, is it not imaginable that Louise

Brunets

around the world continue to be depleted by the skewed economic structures that exploit

them?

.png)